The 2010 ADA Standards: A Landlord’s perspective

Posted on - Monday, August 20th, 2012The Americans with Disabilities Act became the civil rights law for disabled Americans in 1990. Ever since then, the disabled community has been able to get jobs, enjoy independence and become productive members of our society. The ADA is organized in five “titles”. In this post we will focus on the Title III which requires that places of public accommodation and commercial facilities be made accessible to persons with disabilities. We will also touch on Title I which states that a business cannot discriminate against a person with disabilities when they are hiring or firing. They can’t decide not to hire someone or fire someone based on their disability. In essence the ADA makes sure that persons with disabilities get treated equally. So how does a building owner and landlord comply?

Part of the ADA required that places of public accommodation and commercial facilities be made accessible to persons with disabilities. By this mandate, building owners had to make their buildings, new or existing accessible. This requirement was sometimes more difficult than was first thought. For newly constructed buildings, they had to make sure that their architect and contractor understood the requirements otherwise their building would not be in compliance and there could be a risk of complaints or worse, a law suit. Ultimately it is the building Owner’s responsibility to make sure things comply, therefore hiring architects, interior designer and contractors that understand the rules, is a huge help.

There are different rules for new construction and remodels. The rules for new construction are a bit simpler. Whatever you build must be in compliance. It only gets complicated if the new constructed areas are spaces that are not required to comply. Some examples of areas that do not require accessibility are mechanical rooms, telephone equipment rooms and electrical rooms. These are exempted based on the fact that they are considered “machinery” spaces. Those are spaces that only have equipment inside and only periodically gets monitored by an employee.

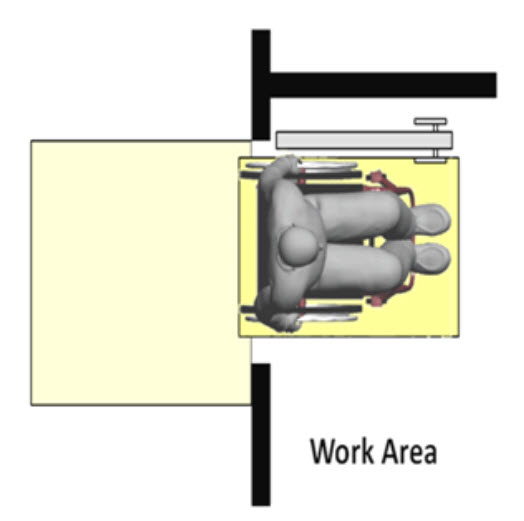

Another area of confusion during design and building are employee areas. Employee areas are not necessarily excempted from having to comply. I hear a lot of building owners say “nobody will ever go back there” when they speak of employee areas. They are correct in making the statement because customers may not necessarily be allowed to go to an exclusively employee or staff area. But what it is not clear is that their employees and staff will be going “back there” and using the facility. This is where Title III of the ADA gets intermingled with Title I. Title III recognizes that not every employee will need the facility to be accessible at the time construction is complete and that the business may not have a disabled person working there. Therefore they are not required to provide accessible “work areas” or areas where the work is happening at the time the project is finished. As soon as a disabled person wants to work there, or if (G-d forbid) an employee becomes disabled while working there, accommodations will have to be provided. Thus the work areas are exempted from the Title III of the ADA except for the ability to approach the area, enter the area and exit the area. For example, if there is a stock room or a copy room in an office space, those are considered work areas and only require approach, enter and exit. The elements within the space, such as counters and shelving or even sinks, will not be required to comply.

But it is not ALL employee areas. This exemption is only allowed to be taken for work areas. Therefore employee restrooms or employee break rooms are not exempted and must be accessible. The reason is that these spaces are not part of the job description, but rather where they take breaks from work. Private offices that have restrooms inside them, are also exempted for certain elements. The restroom should have the proper clearances, but grab bars, knee space at sinks and knee spaces at sinks will not be required at the onset.

The next type of construction is an alteration. This type of construction is a bit more complicated to decide what is required and what is not. The first thing one has to determine is what area of the building is being remodeled or altered. Does the area contain a primary function of the space? If it does not, such as a restroom or a storage room for example, then only the new elements must comply. So if a new paper towel dispenser in a restroom is getting added, or even if an entire restroom is getting remodeled, only the restroom must comply and nothing else outside the restroom, including the entrance to the restroom. But if the answer is that yes, the area being altered contains a primary function, then the new elements and spaces must comply but in addition to the new elements, existing path of travel from the main entrance of the building must also comply. If the existing path of travel contains restrooms, drinking fountains and public telephones, those also must comply with the ADA Standards. In Texas, the Texas Accessibility Standards added parking to the list. Therefore the parking that serves the altered area must also be in compliance.

There is a new exception to this rule of the path of travel. If the building owner is leasing the space to a tenant and the tenant is the one who is paying for the finish out, then the path of travel elements within the building that leads to the tenant space does not have to be brought up to compliance if they don’t already comply. If the landlord pays for any of the tenant finish out via an allowance or any other financial means, then the same rules apply for the alteration of a primary function and the path of travel elements will have to be brought up to compliance. Also, if the facility and the elements along the path of travel comply, but they comply with the old Standards (1991 ADAAG or 1994 TAS), then those are considered a “safe harbor” and also do not have to be brought up to compliance.

If during the alteration, it is discovered that the upgrade to the elements found along the path of travel would cost more than 20% of the total construction cost, the Department of Justice considers it “disproportionate”. Due to disproportionality, the DOJ allows a postponement to the upgrades. If the upgrades will be postponed, the DOJ requires that certain things be done in a certain priority level. Costs that may be counted as expenditures required to provide an accessible path of travel may include:

1) Costs associated with providing an accessible entrance and an accessible route to the altered area, for example, the cost of widening doorways or installing ramps;

2) Costs associated with making restrooms accessible, such as installing grab bars, enlarging toilet stalls, insulating pipes, or installing accessible faucet controls;

3) Costs associated with providing accessible telephones, such as relocating the telephone to an accessible height, installing amplification devices, or installing a text telephone (TTY); and

4) Costs associated with relocating an inaccessible drinking fountain.

The DOJ has established a priority list of items that are required to comply and what priority to give them. A building owner may not decide to fix the door hardware of interior doors before they fix the main entrance. In choosing which accessible elements to provide, priority should be given to those elements that will provide the greatest access, in the following order:

(1) An accessible entrance;

(2) An accessible route to the altered area;

(3) At least one accessible restroom for each sex or a single unisex restroom;

(4) Accessible telephones;

(5) Accessible drinking fountains; and

(6) When possible, additional accessible elements such as parking, storage, and alarms.

Sometimes the best efforts finds that access cannot be accomplished because existing structural conditions would require removing or altering a load-bearing member that is an essential part of the structural frame or because other existing physical or site constraints prohibit modification. In those cases, speaking to local authorities and the DOJ to get a variance or waiver might be the proper action to take. But even if it is not possible to provide access for wheelchair users, the building owner is still required to make sure other disabilities are accommodated. Accommodations in buildings should be provided for the visually impaired, hearing impaired and people with other mobility issues such as walkers, crutches and braces.

With all the complicated rules and regulations that we might encounter during the design process, it is important to keep in mind the big picture. What was the reason for all this extra effort? Before the ADA was enacted, a person with disabilities was relegated to stay home or in an institution. They depended on others for transportation and for every day tasks. The ADA was enacted to encourage and promote the rehabilitation of persons with disabilities, to eliminate unnecessary architectural barriers for persons with disabilities, to not restrict the ability to engage in gainful occupation and to not restrict the ability to achieve maximum personal independence. As building owners we must keep in mind our customers and how at the end of the day we are opening our doors to a large portion of the population that wasn’t thought of before. And the struggle will continue as Americans age and as more of us become disabled. But these guidelines are universal. When we remove barriers for one group, we are essentially removing barriers for everyone. And the more architectural barriers we remove, the more cultural and social barriers we remove as well.

This post was published in the CREST Publications’s Network Magazine September 2012 edition

Abadi

Abadi